Scourging

Below are some details about the scourging/flogging process of Romans and others:

Roman Scourging

This is from the article “On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ”, written by William D. Edwards, MD, Wesley J. Gabel, MDiv, and Floyd E. Hosmer, MS, AMI, and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in April 1986, 1455-1463:

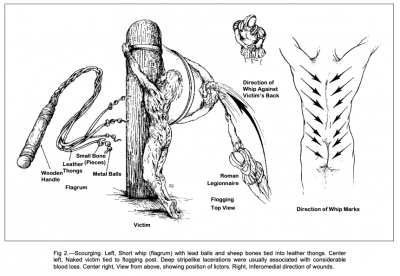

Flogging was a legal preliminary to every Roman execution, and only women and Roman senators or soldiers (except in cases of desertion) were exempt. The usual instrument was a short whip (flagellum or flagellum) with several single or braided leather thongs of variable lengths, in which small iron balls or sharp pieces of sheep bones were tied at intervals (Fig 2). Occasionally, staves also were used. For scourging, the man was stripped of his clothing, and his hands were tied to an upright post (Fig 2). The back, buttocks, and legs were flogged either by two soldiers (lictors) or by one who alternated positions. The severity of the scourging depended on the disposition of the lictors and was intended to weaken the victim to a state just short of collapse or death. After the scourging, the soldiers often taunted their victim.

Medical Aspects of Scourging

As the Roman soldiers repeatedly struck the victim’s back with full force, the iron balls would cause deep contusions, and the leather thongs and sheep bones would cut into the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Then, as the flogging continued, the lacerations would tear into the under lying skeletal muscles and produce quivering ribbons of bleeding flesh. Pain and blood loss generally set the stage for circulatory shock. The extent of blood loss may well have determined how long the victim would survive on the cross.

“On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ”, written by William D. Edwards, MD, Wesley J. Gabel, MDiv, and Floyd E. Hosmer, MS, AMI, and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in April 1986, 1455-1463

Figure 2 referenced in the above article (click to enlarge):

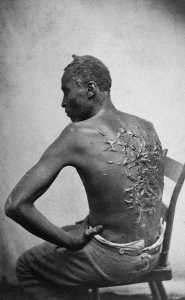

The photo below is of Gordon, who was a slave in the South. The scars are from the beatings he received from his masters before his escape in 1863. The image is sometimes titled ‘Whipped Peter’ and was part of a series of iconic images used to make the horrors of slavery known. It shows us what the result of scourging may have looked like and also that such horrific violence and torture does not only belong to ‘ancient history’ or other cultures but has very much been present in our own.

A Description of Roman Scourging From Josephus

Josephus describes the scourging of a man (Jesus, son of Ananus) who predicted the fall of Jerusalem. This was in the late fifties early sixties AD (20-30 years after Jesus Christ):

But, what is still more terrible there was one Jesus, the son of Ananus, a plebeian and a husbandman, who, four years before the war began, and at a time when the city was in very great peace and prosperity, came to that feast whereon it is our custom for everyone to make tabernacles to God in the temple, (6.5.3) began on a sudden cry aloud, “A voice from the east, a voice from the west, a voice from the four winds, a voice against Jerusalem and the holy house, a voice against the bridegrooms and the brides, and a voice against this whole people!” This was his cry, as he went about by day and by night, in all the lanes of the city. (6.5.3) However, certain of the most eminent among the populace had great indignation at this dire cry of his, and took up the man, and gave him a great number of severe stripes; yet did not he either say anything for himself, or anything peculiar to those that chastised him, but still he went on with the same words which he cried before. (6.5.3) Hereupon our rulers supposing, as the case proved to be, that this was a sort of divine fury in the man, brought him to the Roman procurator; (6.5.3) where he was whipped till his bones were laid bare; yet did he not make any supplication for himself, nor shed any tears, but turning his voice to the most lamentable tone possible, at every stroke of the whip his answer was, “Woe, woe to Jerusalem!”

(War 6.300–304 JOSEPH)

Scourging, Mocking, and Hanging: Dio Chrysostom’s Depiction of Persian Practices

Dio Chrysostom, a Greco-Roman orator, writer, philosopher, and historian of the first and second-centuries AD, wrote the following about the practices of the Persians in mocking and crucifying victims. Though the narrative is placed 300+ years before Jesus and in a Persian rather than Roman context, the similarities of the process of mocking, beating, and hanging someone who might make false claims of kingship to the narrative in the gospels about the suffering of Jesus, mockingly crucified as ‘King of the Jews,’ is insightful for what perhaps happens across cultures when powerful forces punish with such claims:

“Well, they take one of their prisoners,” he explained, “who has been condemned to death, set him upon the king’s throne, give him the royal apparel, and permit him to give orders, to drink and carouse, and to dally with the royal concubines during those days, and no one prevents his doing anything he pleases. But after that they strip and scourge him and then hang [suspend] him.” Now what do you suppose this is meant to signify and what is the purpose of this Persian custom? Is it not intended to show that foolish and wicked men frequently acquire this royal power and title and then after a season of wanton insolence come to a most shameful and wretched end? And so, when the fellow is freed from his chains, the chances are, if he is a fool and ignorant of the significance of the procedure,that he feels glad and congratulates himself on what is taking place; but if he understands, he probably breaks out into wailing and refuses to go along without protesting, but would rather remain in fetters just as he was. Therefore, O perverse man, do not attempt to be king before you have attained to wisdom. And in the meantime,” he added, “it is better not to give orders to others but to live in solitude, clothed in a sheepskin.”

Dio Chrysostom Or. 4.67-70,

trans. of Cohoon/Crosby, Dio Chrysostom, 1.199-201